At many Australian universities, July is Expression of Interest (EOI) season for Australian Research Council Grants. For most ECRs this means the beginning of the long process of applying for the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow; the Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA). In this post Meggie Hutchison talks all things DECRA with successful winner Dr Benjamin T. Jones. He discusses the process of refining his topic, finding the best institution for his project, and how to respond to rejoinders. Benjamin also gives some great tips on when to apply, how many publications you will need and offers wonderful advice from his personal experience on what to do if you don’t win a DECRA. For all ECRs applying in the next round of ARC grants and for those awaiting results for this round, we wish you the best of luck!

Benjamin is an Australian Research Council DECRA recipient working in the School of History. He has taught history at the Australian National University, University of Sydney, University of New South Wales, and Western Sydney University and held Visiting Fellow posts at Indiana University and Durham University. He has also worked as a historian at the Museum of Australian Democracy. Benjamin has a broad range of research interests including Australian and Canadian colonial histories, republicanism, Australian nationalism, secularism, and pedagogical theory. He is the author of This Time: Australia’s Republican Past and Future (Redback, 2018), Atheism for Christians: Are there lessons for the religious world from the secular tradition? (Wipf & Stock 2016) and Republicanism and Responsible Government: The Shaping of Democracy in Australia and Canada (McGill-Queen’s University Press 2014). He is the co-editor of Project Republic: Plans and Arguments for a New Australia (Black Inc 2013). He is currently editing a new collection of essays on seminal Australian elections. Dr Jones was the lead researcher of the Alternative Australian Flag Survey.

Meggie Hutchison: What do you love about being a historian?

Benjamin T. Jones: I think the most fun thing about being a historian is storytelling. I think everyone loves being that person at a party who can tell this wonderful anecdote, and it’s partly the small details as well that the historians eye picks up that really brings stories to life. Recently I’ve read Tom Griffiths, amazing the Art of Time Travel. One thing I love about Tom’s histories in general, but especially in this book, is the way he points out that history is an art, and I think sometimes we get bogged down in this really hardnosed historical methodology. I think that’s the real history and the storytelling aspect of it.

That’s the arty insignificant thing. But I think that’s what makes history beautiful. When you have this sort of eye for details. I wrote an article recently on the currency lads and lasses. The first white Australian born men and women and their sense of identity as being British but born in Australia. The first generation.

It could seem an insignificant detail, but they played this cricket match between the Australian born and the British born Australians and they got so worked up about it. There was a dubious leg before wicket call and the Australian batsman was challenged to a duel to settle it. It’s just these little details that make the stories of history so engaging.

I could go on about how it’s this conversation between the past and the present which I think it is. But I really love telling stories. And I love the empowerment you get as a historian. It’s that you’re not just relying on other people’s stories, you have got the toolkit and you have got the ability to go into archives and to make sense of all these figures and documents. And you can discover new stories and tell them. So there’s a real pleasure in that.

Meggie: I wanted to ask about the questions that drive your research. Do you have any burning questions that have led you to your topics?

Benjamin: Yes. Absolutely. My main interest is in Australian nationalism. Well, I’m an Australiainist first and foremost, although I do a lot of comparative transnational histories. I’m interested in nationalism, especially republicanism. So I guess some of the driving questions for me is just, how did Australia ended up the way it is? How do you have a country that on the one hand is so proud of its multicultural diverse, open, tolerant society, but it’s also cool with having a giant union jack. Establishing sort of this Anglo Celtic privileging.

How do you get a country that is so staunchly independent and competitive with other nations and especially with the UK, but it’s also very comfortable having it’s head of state being the monarch of a foreign nation. How do you get a country like Australia and its history is sort of baffling in some senses. It is so democratic in some cases. It’s the most democratic nation in the world. In introducing the Australian ballot and all these different things. But then it has this obviously undemocratic way of choosing its head of state. I suppose those are the questions that drive me. How did Australia turn up as this sort of funny bag of contradictions that it is.

Meggie: Do these questions stem from your PhD or further back?

Benjamin: Further back actually. From my honours thesis really. I looked at the republican campaigns in the 1850s and compared it to the 1990s. I grew up a little bit in the 80s but mainly in the 90s and the 90s was a huge period of Australia questioning its identity. It kicks off with Paul Keating having this very strong vision that Australia needs to reimagine itself as part of Asia. As a republic and losing the baggage of imperialism and British colonization and all the rest of it.

Australia has almost this 180 degree turn in 1996 when John Howard comes in. Someone who couldn’t be more different in their approach. And so a lot of historians who I admire, Mark Mckenna’s right up there, John Hirst is right up there. Writing these amazing books in the 1990s all about identity. I suppose even though I was a teenager in that period, these ideas are just in the air and that’s when I did go through university, it’s what I wanted to research.

Meggie: Can you tell us about the topic of your PhD?

Benjamin: My PhD is called ‘Commonwealth of Republics’ and it currently sits on my dad’s desk where it props up his monitor to just the right height that he likes it, so I’m glad that it’s gone to good use! I was inspired somewhat by my honors supervisor, Professor Melanie Oppenheimer, to look at Australia, Canada comparative studies. She’s done a lot of that research on WWI. Comparing volunteers and different things. When you look at just the mountain of books there are comparing Canada and the United States, it’s kind of amazing that there’s so few because Australia and Canada are actually better comparisons in many regards, but not that many historians have looked at it.

My particular angle in my PhD was to compare the granting of responsible government in Canada and then in Australia. It did end up getting published as a book called Republicanism and Responsible Government through McGill-Queen’s University Press and let that be lesson number one to aspirational DECRA people, don’t be modest and plug your work whenever you get the chance!

Meggie: Good lesson! What’s the subject in the DECRA then?

Benjamin: It’s called ‘Aristotle’s Australia’ and I’ve moved from the 19th century into the 20th and it’s a history of civic republican thought from federation to modern times.

Meggie: What’s the process by which you arrived at this project? You’re moving into a different century, but are there direct links to your previous research?

Benjamin: Yes, a different century but the same ideas. I did very consciously approach the DECRA by saying, “Not only do I think this is a good topic, but I also think that I’m the right person to write it”. So, to that end I drew a lot of links straight from my PhD and I almost pitched it as this is going to be volume two. Staying on the same themes and looking at a different time period, but building on a lot of the strengths and a lot of the archival work that I’ve already done. Certainly, in my case it worked to very strongly say how this project is a natural progression from my PhD.

Meggie: We’re always told that we have to create a strong research narrative for the DECRA. Do you think that’s one of the reasons that you were so successful in yours? Because you could make that kind of connection?

Benjamin: I think so because you leave yourself a little bit vulnerable if you just invest in creating a really great topic but not making it obvious why you’re also the natural person to do it. I can understand people having a bit of research fatigue. It’s a long journey to complete a PhD and you may feel like great, now I’m going to go off to my “love project”, as people sometimes put it. But if you’ve invested so many years and so much time researching a particular area, it can be a different topic, but at least if you’re saying I’m going to be drawing on the same methodological principles. Or if there’s at least somewhere to say that the skills you’ve acquired over the last four or five years or however long it took to do your PhD, are still going to be used and in fact are essential to getting this project done, then I think you’re giving yourself a fighting chance.

Meggie: Does your DECRA draw on the comparative element of your PhD as well?

Benjamin: It doesn’t actually. So that’s one difference. I’m using the same themes and the same ideas. My PhD was an intellectual history of ideas. So I’m looking for the same intellectual tradition. But no, I’ve dropped the transnational aspect and that wasn’t so much strategic. I suppose it does make sense for the Australian Research Council to want to fund something that is 100% Australian focused, but it also just sort of naturally ended up that way.

Meggie: Let’s talk a bit about the process of actually applying for a DECRA. You get two shots at it, so what is the best point to apply? There’s advice that two to four years out of your PhD is optimum.

Benjamin: Well, yes, that’s right. If you look at the percentages of people who are successful, it’s sort of virtually no one a year out, a few more, two years out and three and then sort of three and four is the sweet spot so to speak. But of course every person’s different and you may have already have published a couple of books and several articles and you may be ready to apply for a DECRA a year out and people do get them a year out. But I suppose if you went along the traditional sort of academic route, most people aren’t going to have the research backing behind them in their first or second year. So it is, as you say, with only the two shots, you’re playing the percentages if you apply in your third and fourth year out.

Meggie: When did you apply?

Benjamin: In the third and fourth year out. I was as ambitious as anyone and I went to a DECRA seminar on how to apply for one which was run at the ANU in my first year. And they said something like, you should really emphasize your best 10 publications or something like that. And I was there like, I’ve got four publications all up, so I more or less just left. And I thought, okay, it’s not for me yet. I feel like I should have stayed and listened to the rest for future reference!

I got a strong sense anyway that third and fourth year is the right time to apply. In the third year I didn’t get it and I amended it, not greatly I should add, which also is an important point, that there is such an element of chance and luck and whoever happens to assess it or however many other applications that might be very similar to yours. I do think my second application was better but only marginally. Essentially I think I just applied twice and was unsuccessful one year and was successful the next. That might give hope to people who have been knocked back once, it is definitely worth going through the whole circus again.

Probably the biggest change between the first application and the second application, is I applied at a group of eight university and I kind of just took it for granted that its reputation should speak for itself. So I invested really the bulk of my energy into saying, this is a great project. I’m someone worth backing. Please pick me. And also, I’m going to a great institution and sort of left it at that.

One thing that I think I definitely improved on the second one was saying, okay, let me actually show you more. Here’s some of the people who are at ANU. Here are some of the resources that are close by. Here are some of the libraries I can use. I guess you’ve just got to take every section as seriously as the one before. Even that one I felt was a bit of an obvious one. Whether that made a difference, I don’t know. But that’s one thing that was definitely stronger the second time around.

Meggie: Was there anything else you fixed that you think might have made the second attempt sparkle more than the first?

Benjamin: Well, there is this, I applied in the ANU’s Humanities Research Centre which is where I did my PhD. I think a lot of the appeal there was that I was applying so that I could be with people I know and a place that I’m comfortable with, and I wondered whether the reason I’d chosen that was more emotional than for academic integrity. So, I applied through the ANU’s School of History, which I was quite unfamiliar with instead, having made a reassessment that actually this is a better place for the project to be and I can make a stronger argument for being here even though I won’t be with my friends.

Meggie: So the research environment is very important for a DECRA.

Benjamin: Yes, absolutely. It’s definitely not as simple as just saying, I’ll apply for at a group of eight university. They’re the ones with the reputation depending on. And all these projects are so individual and probably if you’re serious about it, you need to get some people who are going to read your application closely because this is all good general advice, but you do need people who can tailor the application specifically to you.

But there are all sorts of reasons why a regional university or a university that has a particular center or a particular school might be the perfect place to do whatever the project is. It definitely would be lazy to just think, well, I’m just going to pick whoever is highest in the rankings this year as my home.

Meggie: How do you choose your institution?

Benjamin: Well, I looked first at a geography. You’ve got a limited budget and of course you can fly places but you’ve got to stay in hotels and all that sort of thing. So wherever the bulk of the archival material or the field work stuff is, is really where you want to be. In my case, Canberra just in general was the first idea. I was in Sydney at the time, which obviously has a lot of great archive as well but I made a conscious decision that Canberra was going to be the best place first off. Then which university in Canberra was a secondary decision. But having already so many contacts at the ANU, it sort of seemed like an easy choice in that sense as well.

Meggie: There’s so much speculation and rumour about how many publications you should have when you apply. What’s your advice on that?

Benjamin: When I applied I had about 10, so I still wasn’t in the position of picking my best 10. I just put them all. I suppose that is ideal. It certainly is a case that quality is better than quantity, but I think all ECRs should think seriously about co-publishing a couple of things. I published an article with my PhD supervisor and another one with one of my close friends who did their PhD at the same time as me as well as publishing a couple of solo ones.

Meggie: Getting your book out before you apply for a DECRA, so as quickly as possible, is often the advice given to ECRs.

Benjamin: Yes, and it’s a shame. If I’m giving advice it is just get it out as quickly as you can almost with whoever will publish it. I think that’s a real shame. In retrospect I wish I’d actually had the luxury of taking five or so years to just not even think about my thesis and then go back and really enhance it and make it a more superior document. Reading back over it now, it kind of screams recent graduate, but such is life. I guess it’s a historical record of where I was at the time.

Meggie: What’s the first thing you do when you decide on your DECRA topic?

Benjamin: Well, be realistic about how long it takes to write a DECRA application I think is probably the first thing. The best advice I had actually was to think of it as being as much effort and time and energy as writing a journal article and going in with that sort of mindset. This isn’t just a job application you’re going for. It is quite a serious research proposal. If you go in thinking, “Okay, I’m not going to finish this in one or two nights,” then that’s a good starting point.

The way I did it was to look through the entire document and put one or two sentences under each thing and start to collect my thoughts about the project as a whole and to make sure I was happy with it. I pitched it to a few friends and a few colleagues, got their advice and then went for the project description first and again circulated that to various people and received edits on it.

Meggie: What about the budget? Did you have any help?

Benjamin: I didn’t and should have is the short answer. I thought I was doing myself a big favour by having a really modest budget and I cut every little corner I could and said I’d stay in the cheapest hotels and find the most budget. But the feedback I’ve got since is that they’re not going to judge you more harshly if you have a bigger budget, so long as the items are the normal things that people would expect.

If it’s something unusual, obviously justify it is important. Another successful DECRA applicant told me casually down the corridor that they just applied for as much money as the maximum amount and then worked backwards from there. So, in retrospect maybe I should’ve done that. Although one of my assessor’s reports comment on my frugality. Maybe it impressed someone a little bit, but I think you should actually feel safe to say I’m going to claim as much as I need.

Meggie: How did you go about “selling” the value of your DECRA and its relevance to Australia today?

Benjamin: It’s a funny question because I’m definitely working on a love project. I guess I can give hope to people who have just one project which is the only topic they want to write about that it is possible. But I suppose by the same token, right back from my honours year (again, I’ve always had good people giving me good advice) I knew that I should gear my project towards subjects that are going to be relevant and areas that are likely to get funding.

You certainly have to keep in mind that this is the Australian Research Council and they have a specific mission to advance knowledge on Australia and to fund research that is going to help in its strategic areas. So you need to at least be aware of those strategic areas. You need to be able to pitch it in such a way that this is going to be of the greater good of our Commonwealth. But there is a very broad understanding that the historical projects are just as valuable as combating climate change.

It may not feel that way, but I think sometimes the humanities has this inferiority complex. Like we’re the least important and we deserve the least funding and we matter the least. It really is a self-fulfilling prophecy sometimes. I think it is fundamentally important to the health and vibrancy of our nation that there are people out there researching Australian history and telling Australian stories. It’s important and it should be pitched that way. It’s in the national interest of Australia that I complete this research and I stand by it.

Meggie: How did you do that with your DECRA application?

Benjamin: Well, I framed it as gaining a better understanding of Australian politics, Australian identity. Australia’s place in the world was probably the one that most aligned with the ARC. Saying that Australia has fundamentally shifted the way it imagines itself from being this British white European outpost to this vibrant, multicultural nation in the Asia-Pacific region, and how civic republicanism has shaped the way Australians think about themselves. And this has all sorts of repercussions to how we teach history in schools and how we present ourselves on the international stage.

Meggie: How did you approach the feasibility of the project which is an important part of the application?

Benjamin: I think the rules may even have changed since I did it. It used to be sort of equal weighting to the project, to the individual and to the institution. But I suppose even if it has changed, the idea is that every section needs to be taken incredibly seriously. It needs to have the same thoughtful, intelligent, coherent answers throughout. In terms of feasibility though, that was something where I seemed to get particular ticks from the assessors.

So it is important to say that this is a project you have the ability to do. You need to almost go back and look at the project description and the aims and the outcomes and possibly reign it in a little bit if you’ve been perhaps too grand. You should think about how much you achieved during the three years of your PhD and use that as a starting point. Certainly, you’ll be doing work at a higher quality than junior PhD candidacy. But it does give you a little bit of realism in how much is actually possible.

Of course you have to factor in that if you go to a new institution and perhaps you’re wanting to eventually get some sort of secure employment there at the end, then it’s going to be worth your while to be a good academic citizen and you should factor in that. You may find yourself teaching, unless the rules have changed. Is it up to 20% of your time you can spend teaching? But just general collegiality. You’re going to be giving guest lectures, you’re going to be giving seminars, you’re going to be helping run conferences.

All these things are really, really good for a DECRA applicant to be doing. But you’ve also got to think that these are things that are going to take away your research and writing time as well. So have that in mind when you’re thinking about how much you can realistically do because, especially if you get it, you’ll feel a lot better about yourself if you can actually tick off the things you said you were going to do and it certainly will improve your chances of getting another ARC discovery in the future if you can point back to a successful DECRA and say, look, I said I was going to do X, Y, and Z and I did X, Y and Z, and now here’s my new project.

Meggie: What are your outcomes from your DECRA?

Benjamin: Well, the centrepiece was certainly that I’ll write am academic monograph. I also highlighted about three different aspects of my research that I thought should also be standalone journal articles. I said I was going to attend conferences along the way, particularly in the early stages so that I could give work in progress seminars. I also requested funding to host a conference towards the end of my project.

I suppose I should reiterate. Don’t be shy about sending it to people. One of the things that really was great for me was getting so many people say that it was a manageable project. It just gives you that confidence to say, okay, well people I know and respect think this is a good project. They think it’s a good application. I can put it forward now, if it gets rejected, it’s not going to break my heart that much. I’m not going to completely lose my confidence because I know that people I know and respect have said that it’s okay.

Even though it’s not ideal, if you fail to get a DECRA twice, you really should just do the project anyway, though it’s difficult if you’re not going to get that particular funding. There are still other funding sources and there are ways to do it. But if you’ve invested that much time in developing a really great project, you really should have that resolve that this is getting done one way or the other and that’ll probably even improve the language of how you write the application.

Meggie: I wanted to ask about the rejoinder. How important is it and can it make or break your success in getting a DECRA?

Benjamin: I think it definitely can. Much more than the application actually, it gives a little insight into the applicant’s attitude and personality. I think certainly if you came back really indignant, then that’s not going to be a good look.

But by the same token, I don’t think it’s a great look either to just be like, “Oh yes, you’ve called me. It’s useless, it’s terrible. I’ll just withdraw.” You do have to sort of find the sweet spot where on the one hand you’re saying “I stand by my application, I stand by my project and this is a worthwhile thing”. But also on the other hand conceding as much as you can where you see legitimate chinks in the armour that could have been strengthened.

My basic approach, which I think was effective, was to read really carefully what they said and to almost write it back in the rejoinder. I started off with, “I am so glad that review A said X, and I’m so glad that review B agreed and said Y”. I pointed out a few things where there were criticisms that I could have mentioned this or that. I politely said review B raised this issue. However, on page 23 of the application I did address that. Adding in for modesty that I could have made this clearer or longer or whatnot.

It’s sort of tight rope between showing you’re someone who believes in themselves, but are also someone who can take criticism constructively. But I think it is really a serious part of the process. In the same way that you should get people to read over your application, I definitely wouldn’t just quickly write it. I had at least three people read my response and then also people from the research office and I edited it reasonably substantially actually from those comments. So yes, the rejoinder is very important.

Meggie: I also wanted to talk a little bit about failure. You were successful on your second attempt, but how did you deal with not getting a DECRA on your first try?

Benjamin: My personal process is actually very similar to a rejection to a journal article, which is to quickly read it and then just ignore it. Just do something you enjoy. Go for a run, watch a movie. I usually have to leave it for a week or two and to come back when I’m calm and I know it’s a rejection but I’ll read it. But just having that little bit of space really helps.

It really helps you discern between what might be the more reasonable criticisms and other criticisms which you have to just say, well I disagree with that and I’m going to more or less a reapply with the same ideas. But as much as you can take the emotions out of it, be as stoic as you can. I guess it’s like anything else in life, getting rejected from a job or something. If your passion is to be a historian, then you have to just move forward with it.

Meggie: Was there a plan B that you had in mind?

Benjamin: I had a few plan B’s in my time. I actually went through the whole process to become an education officer in the army, so I think I’m technically still in the pool of applicants to be drawn on. Although I probably would have to decline now if they came back to me. That was one, I did do a teaching degree as well. So I’ve also got high school teaching as a fall back plan. But as long as academia is still paying the bills in one way or another, it is where I want to be. But yes I do have plan Bs and it’s probably not a bad idea to have them.

Meggie: OK, one more question. If you could have dinner with anyone from history, who would it be?

Benjamin: I find this question deceptively difficult because the way I approach it is why am I having dinner with them? If it was purely for the pleasure of their company, I’d pick someone like Oscar Wilde. Just because he would be charming. But if it was for my own research so that I could have an exclusive interview (and yes, I know I overthink this way too much) then it would be someone like John Dunmore Lang so he could tell me about republicanism in the 19th century.

But if it was more so I could be a time traveller going back to warn people about the future, then I’d probably pick someone like Robert Menzies and just say, “you need to drop the British stuff. I know it seems like your whole world in the 1950s, but in only two decades, there’s not going to be a British empire. Nobody’s going to think the way you do and you’re going to be the most successful prime minister, but also remembered as this kind of dinosaur who makes comments about being in love with a 20-year-old queen!”.

Agonistic worldmaking

Agonistic worldmaking

University of Western Australia Publishing (UWAP) is one of the most significant university presses in Australasia. A book published through UWAP is a mark of esteem for historians. Its catalogue makes Western Australian histories prominent among a diverse selection of publications so deep and rich that choosing to name a few luminaries feels invidious.

University of Western Australia Publishing (UWAP) is one of the most significant university presses in Australasia. A book published through UWAP is a mark of esteem for historians. Its catalogue makes Western Australian histories prominent among a diverse selection of publications so deep and rich that choosing to name a few luminaries feels invidious.

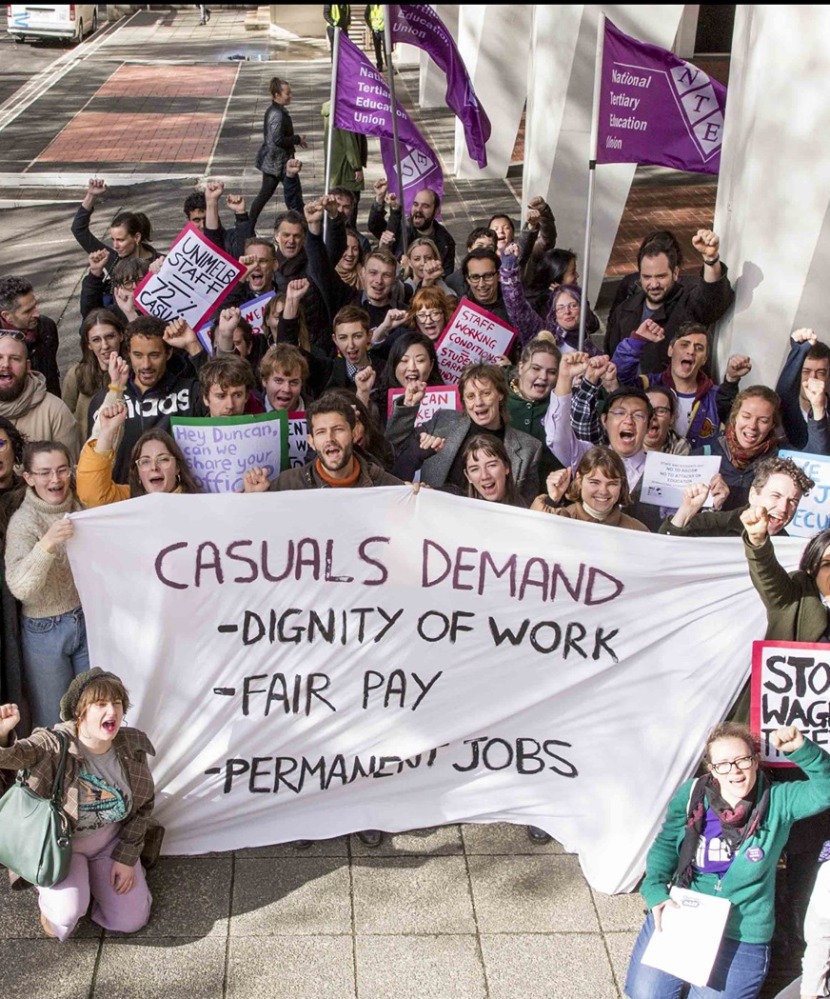

Please note that in the survey, “casual position” is understood broadly, so to encompass all employment that is not ongoing/permanent/tenured. This encompasses fixed-term, full-time, and hourly employment, and all other forms of precarious labour.

Please note that in the survey, “casual position” is understood broadly, so to encompass all employment that is not ongoing/permanent/tenured. This encompasses fixed-term, full-time, and hourly employment, and all other forms of precarious labour. For the past six summers I have worked as a tour guide in Hobart, taking guests from the cruise ships that visit our harbour out to experience some of southern Tasmania’s heritage, culture and food. This was a welcome break as I researched and wrote my thesis. But it was more than a change of scene. I started tour guiding and my PhD in the same summer, and I quickly found it to be an extension of my academic work. With limited opportunities for teaching within the university, guiding is an effective place to practise communicating complicated concepts to the most general of audiences.

For the past six summers I have worked as a tour guide in Hobart, taking guests from the cruise ships that visit our harbour out to experience some of southern Tasmania’s heritage, culture and food. This was a welcome break as I researched and wrote my thesis. But it was more than a change of scene. I started tour guiding and my PhD in the same summer, and I quickly found it to be an extension of my academic work. With limited opportunities for teaching within the university, guiding is an effective place to practise communicating complicated concepts to the most general of audiences.

At this time of year many ECRs begin their Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA) journey, scoping out suitable institutions, refining their research projects and drafting EOIs. In Part 2 of our Dissecting the DECRA series, Meggie Hutchison talks to successful DECRA winner Dr Elizabeth (Libby) Roberts-Pedersen about what to do (and what not to do) when developing your application. Libby discusses how her research narrative emerged and the core questions that inspire her work. She also offers some wonderful insights into how she refined and reshaped her project for her second application and talks about what it’s like to research with young children. For all ECRs applying in the next round of Australian Research Council grants and for those awaiting results for this round, we wish you the best of luck!

At this time of year many ECRs begin their Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA) journey, scoping out suitable institutions, refining their research projects and drafting EOIs. In Part 2 of our Dissecting the DECRA series, Meggie Hutchison talks to successful DECRA winner Dr Elizabeth (Libby) Roberts-Pedersen about what to do (and what not to do) when developing your application. Libby discusses how her research narrative emerged and the core questions that inspire her work. She also offers some wonderful insights into how she refined and reshaped her project for her second application and talks about what it’s like to research with young children. For all ECRs applying in the next round of Australian Research Council grants and for those awaiting results for this round, we wish you the best of luck!

You must be logged in to post a comment.